ART & ARCHITECTURE

St Mary’s Church is one of the finest and most complete buildings in England to survive from before the Norman Conquest. The in situ sculpture and painted remains gives us an idea of the sumptuousness that could characterise Anglo-Saxon church architecture. Its architectural history is complex, and many questions remain. Excavations and detailed surveys of the fabric were carried out in the 1970s by a team involving Philip Rahtz, Harold Taylor, Lorna Watts and Lawrence Butler. Their conclusions have recently been reappraised, and a substantial part of the building is now considered to belong to the early 9th century (between the 790s and 830), around the time that Deerhurst benefitted from the patronage of Æthelmund and Æthelric (see Historic Development).

The Anglo-Saxon church

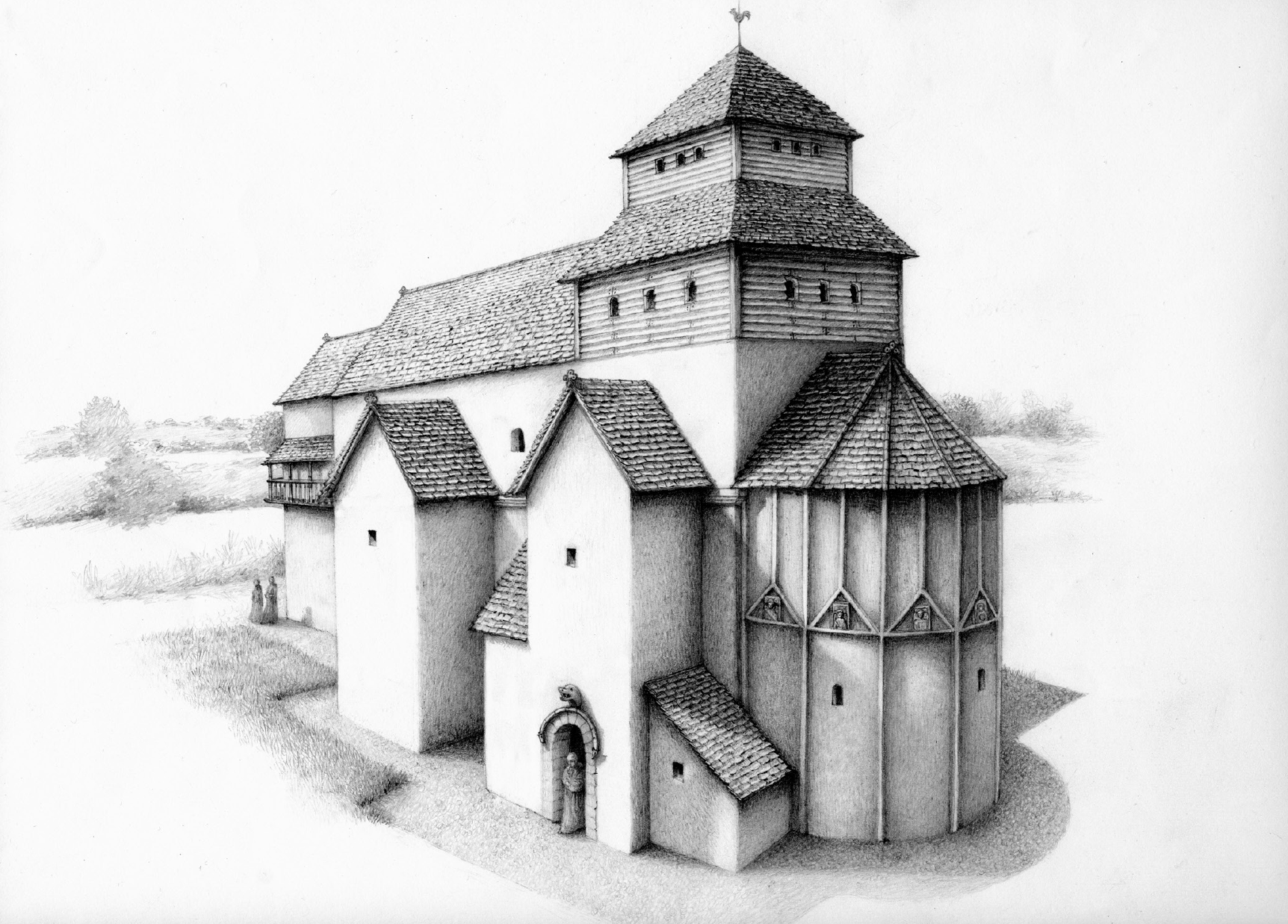

When first built, the church was planned with a central nave and choir corresponding to the high-roofed central space that we see today; this was originally divided into two separate spaces by a wall on the line of the present chancel steps, with the nave opening to the choir through an arch similar to the blocked arch which can be seen in the east wall. The blocked arch in the east wall opened to a seven-sided apse built on a semicircular foundation. The apse contained the principal altar, probably with seating running round the wall of the apse for the clergy during the celebration of the mass. There were two-storeyed annexes (termed porticus) flanking both the choir and the nave to north and south. There was also a three- or four-storeyed west porch, with an elaborate high-level chapel and an external balcony. The substantial blocks of oolitic limestone used for arches, doorways and other features at Deerhurst were doubtless brought from the Romano-British town (a colonia) at Gloucester, and possibly other sites including villas at and around Deerhurst.

Reconstruction of St Mary’s church, Deerhurst, in the 9th century, seen from the south-west. Drawing by Maggie Kneen: copyright reserved.

Influences

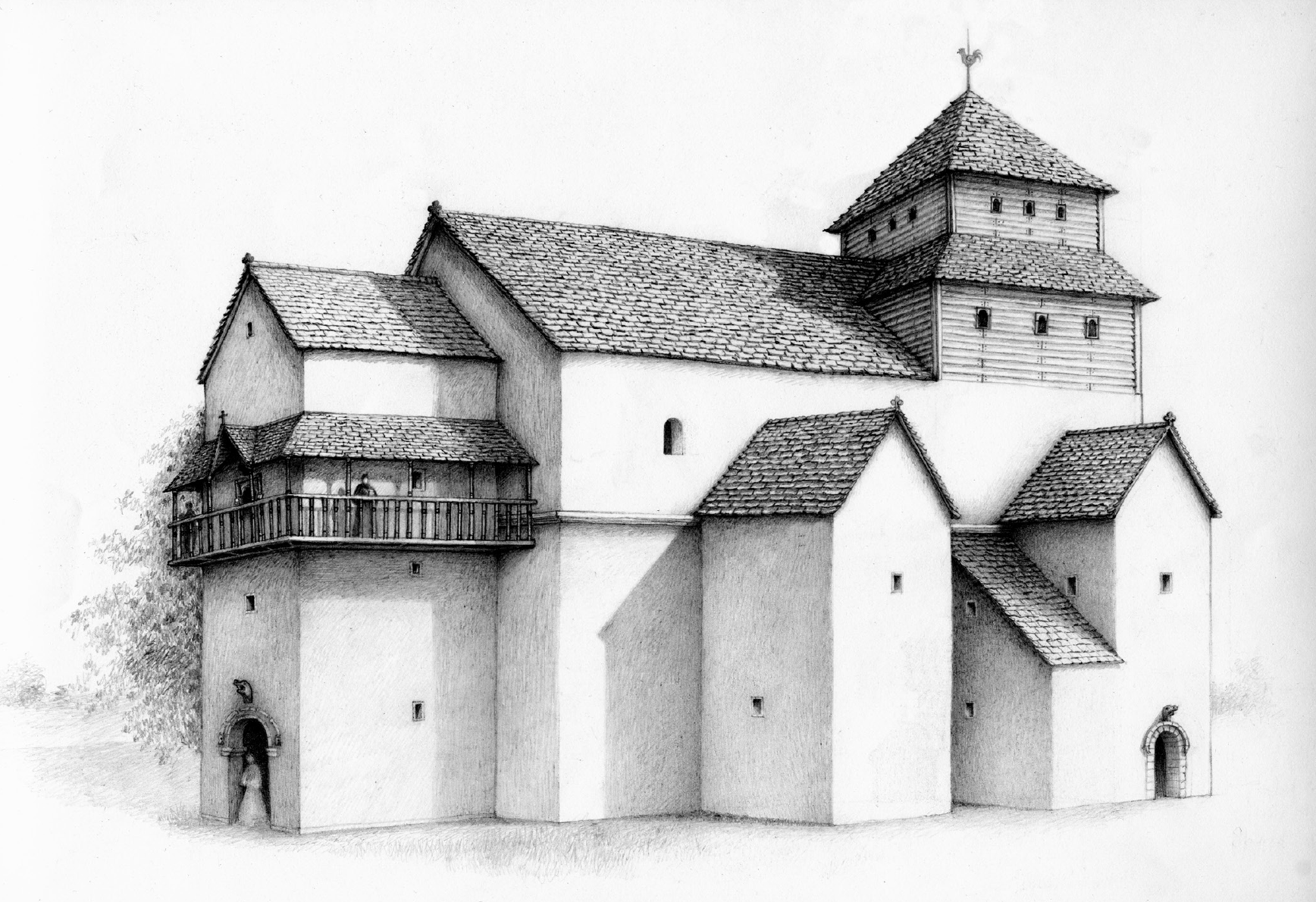

In the art and architecture of the building we can discern a mix of Anglo-Saxon, Roman and Byzantine influences. Polygonal apses derive from the Byzantine world, transmitted to the west via Ravenna, Italy. The principal altar probably displayed an icon of the Virgin, as contemporary churches dedicated to the Virgin Mary in Rome did (Deerhurst’s patron, Æthelric, will have seen such icons on his pilgrimage c. 804). The porticus are found in other Anglo-Saxon churches; the former existence of those flanking the nave was only recognized as recently as 2012. The porticus to either side of the choir, entered by vestibules, were probably used for storing liturgical books, vestments, chalices, processional crosses, shrines, reliquaries and other treasures; we should envision the early church as glistening with gold and silver. Porticus were also used for burial, which is probably also the case here. The use of the upper storeys of the various porticus is open to debate. The high-level chapel above the porch opened through a doorway to a wooden walkway which surrounded the exterior of the porch on three sides; this walkway may have been used for the display of relics on feast days and perhaps for choristers greeting the procession on Palm Sunday.

Reconstruction of St Mary’s church, Deerhurst, in the 9th century, seen from the south-east. It is likely that the polygonal apse was ornamented by a sculpture of the Virgin and flanking angels – of which the ‘Deerhurst Angel’ survives. Drawing by Maggie Kneen: copyright reserved.

Detailing

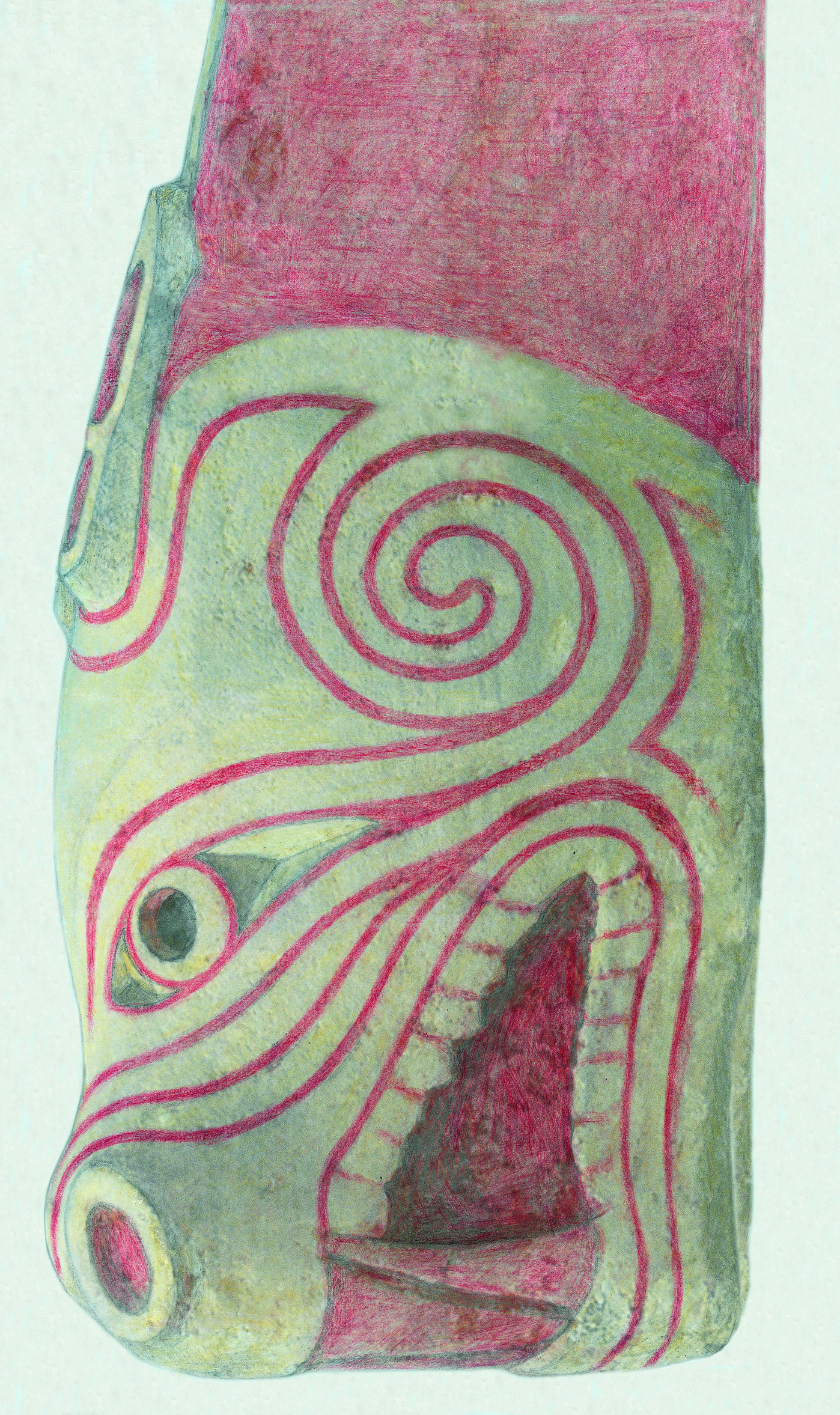

There is a remarkable series of carved beasts’ heads, of a type commonly encountered in illuminated manuscripts and in metalwork but virtually unknown in architecture of the period; they are likely to derive from the decoration of timber buildings such as the great feasting halls erected by members of the Anglo-Saxon elite. The two large projecting beast-heads above doorways in the west wall of the porch are especially striking, though weathered and damaged. Internally several of the beast-heads retain traces of original paint of 9th-century date, remarkably well preserved in the case of the beast at the north side of the blocked arch leading to the apse; the painted detail on this beast-head is closely comparable to the two carved smaller beast-heads visible on the east side of the central doorway in the porch which themselves retain traces of paint.

One of the two beasts’ heads flanking the west door to the nave. These were discovered in 1861 in the blocking of the triangular-headed doorway on the north side of the choir; they show some signs of weathering so are likely to have been external.

Sculpture and Font

The carving of the Virgin and Child above the inner west door also retains slight traces of paint. Originally this sculpture must have been painted to show the Virgin holding a shield on which the Christ child was painted, symbolizing the child in her womb. The oldest examples of this iconography date to the 6th and 7th centuries in the Byzantine world, but it was also used in two 8th-century papal commissions in Rome. It is likely that Æthelric saw images of this type on the occasion of his visit to Rome, and that it was this pilgrimage which led to the appearance of this iconography at Deerhurst, otherwise unknown in northern Europe. Other 9th-century sculpture includes the famous ‘Deerhurst Angel’ in the ruined polygonal apse; the closest parallels for the figural treatment are found in the evangelist portraits in the Book of Cerne, a Mercian manuscript of 9th-century date. The apse may originally have had a spiritual guard of seven angels (perhaps archangels), one in each bay, or alternatively the Virgin as queen of heaven flanked by six angels. The elaborately decorated font also belongs to the early 9th-century church, though scholars disagree as to whether the bowl was originally made to serve baptismal purposes. The stem which now supports the bowl was perhaps originally part of a round-shafted cross, and similar spiral ornament survives at the nearby church of Elmstone Hardwicke (probably a memorial to Ealdorman Æthelmund) and on the 9th-century high cross at Kinnitty (Co: Offaly, Ireland).

Reconstruction of the paintwork to one of the beasts’ heads flanking the chancel arch.

The font, with its distinctive double-spiral decoration and plant-scroll bands, is set on a circular stem – with beasts’ heads integral to its interlaced patterning – which may have originated as a round-shafted cross.

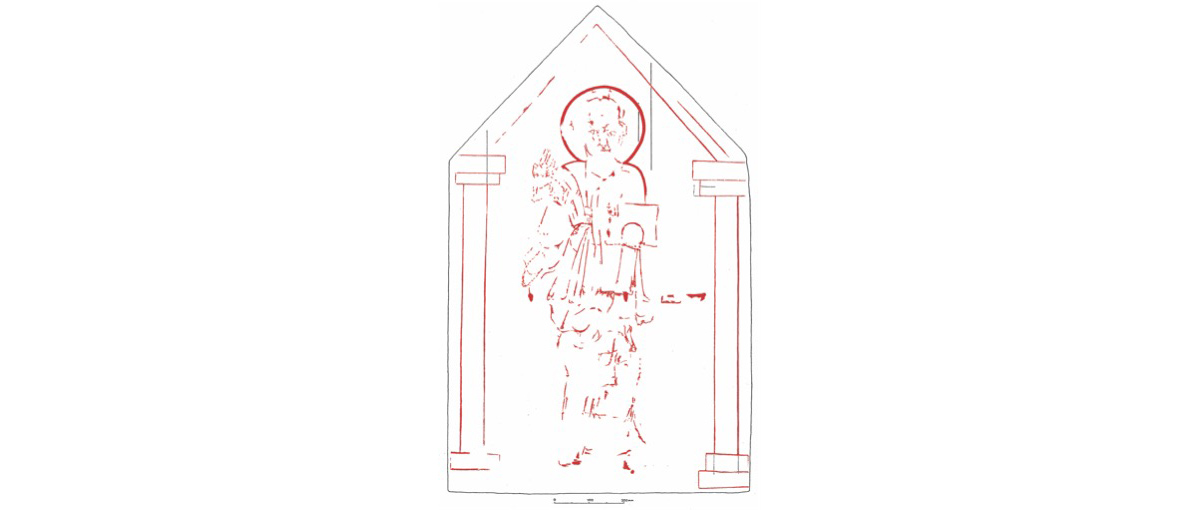

The carving of the Virgin and Child, above the inner west door, still has traces of its original paint. The Christ Child was painted on the shield, and the carving’s Byzantine iconography is of a type which flourished in Rome in a period of Greek-speaking Popes when the iconoclasts (opponents of images) held sway in Byzantium itself.

10th century additions

Some additions made in the mid-late 10th century are visible from inside the nave. These include the two triangular-headed stone panels flanking the high east window, one of which retains the painted image of a saint carrying a book and is probably the oldest known wall-painting in any church in Britain; unfortunately, it is almost invisible from ground level. Another panel of rectangular form is set above a fine double-opening with triangular heads to the chapel above the porch and may be of the same date. A triangular-headed doorway of much poorer quality was inserted between the north choir porticus and the central space, possibly here to allow the passage of a processional cross.

The windows to the chapel above the porch, their pilasters being reused Roman masonry and the central pilaster being an attempt by the Anglo-Saxon builders to evoke Roman models without understanding that the reeds should be placed at the base of the flutes.

Richard Bryant’s reconstruction of the painted figure of a saint carrying a book.

The medieval church

Shortly after the fire of 1100 a segmental arch was cut through the west wall of the former south porticus (now behind the organ); at around the same time a square-headed doorway with jambs of green sandstone was inserted in the south wall of the choir. In around 1180-1200 the Anglo-Saxon nave walls were cut through by Early English arcades, forming aisles to the north and south sides; there are attractive carved capitals, each with a different design. The arches forming a western aisle through the porch were probably inserted to facilitate processions, as part of the liturgy.

The west doorway and some of the aisle windows were rebuilt in the 1320s to 1340s. A private chantry chapel was built at the far end of the north aisle. The central part of the north aisle with its two fine four-light windows was probably built as a Lady Chapel, involving masons who had worked at Gloucester Cathedral; it was originally enclosed by parclose screens. The west window in the south aisle contains at its apex the arms of the de Clare family, probably indicating patronage on the part of the family, most likely by Eleanor (d. 1337). Eleanor was one of three sisters who shared the vast landed estates of the de Clares, who were one of the most important baronial families in the British Isles; the principal residence of the family had been at Holm Hill only two miles north from Deerhurst and their hunting park extended to within a few hundred yards of the priory. These works were followed by the construction of the tower above the early porch, probably extending into the second half of the 14th century.

The interior of the church looking west, as opened out with its arcades in about 1180-1200.

Detail of one of the arcade capitals.

A further series of alterations were made in the late 15th or early 16th centuries. New windows were added to the clerestory and the nave roof rebuilt to a lower pitch; some elements of the roof at the west end survived the 19th century restoration. At around the same time a new doorway leading to the rood loft was inserted. Bench ends in the south aisle have been dated by dendrochronology to 1498–1530, but the original benches were at the west end of the nave. The benches may have been installed primarily for the adoration of the rood (a monumental statue of Christ on the cross above the screen at the east end of the nave), and the rood may have been the focus of all these developments. Perhaps the last alteration to be made before the Reformation was the insertion of four large windows in the south wall of the south aisle, together with a new south aisle roof.

There is a 13th century coffin and 15th-16th memorials including brasses to the Casseys in the north chapel, built as a chantry chapel associated with their home at Wightfield manor. The Cassey family brass of 1400 shows Sir John Cassey of Wightfield manor, Chief Baron of the Exchequer to Richard II, his wife and a dog called Terri at the feet of Dame Alice, the earliest known representations of a named pet in any English church monument. The other two brasses of ladies probably depict members of the Cassey family. The medieval stained glass was collected from different windows and placed in the window at the west end of the south aisle in the restoration of 1861–2; it includes panels depicting St Katherine of Alexandria (c. 1320) and St Alphege (c. 1450).

St Katherine. The exquisite figure of St Katherine with her wheel was originally in the window at the far east end of the north aisle, lighting what became the chantry chapel for the Casseys of Wightfield at the end of the 14th century. This figure may have been commissioned by an earlier occupant of Wightfield manor.

The post-Reformation church

The Reformation was brought about by Henry VIII’s desire to separate from his Spanish wife – first requested from the Pope in 1527 – and establish himself as the Supreme Head of the Church of England. The liturgy became much more Protestant under his son Edward VI (1547-53), and after the reign of Queen Mary and the accession of Elizabeth I (in 1558) it was reintroduced in a moderate form. It brought profound changes to the church and the priory. Part of the priory was retained as a farmhouse after its dissolution in 1540, but its other buildings were either demolished or converted to farm buildings. Along the south wall of the church and the west wall of the adjacent house are corbels which supported the beams of the cloister to the priory. The apse was demolished; in the 18th century a pigsty was built against the east wall of the church, replaced in the 19th century by a cider-house slightly further east (subsequently moved to the east side of the farmyard in the 1920s).

As elsewhere in England, wall paintings were whitewashed over, statues removed, and stained glass windows removed. The rood loft and the rood itself were removed. A remarkable survival at Deerhurst – and the only intact example anywhere – is the early 17th-century arrangement of the chancel, with its fine seating to the north, east and south of the communion table (no longer called an altar). This predates the 1630s reforms of Archbishop Laud, which in seeking to separate the congregation from the celebrant and place the communion table ‘altarwise’ across the chancel were perceived by many to be a return to Catholic practice. Deerhurst was a stronghold of Puritanism, where communicants wishing to commemorate the presence of Christ at the Last Supper sat around the table during the communion service. The rail at the entry to the chancel was probably installed as a sop to the Laud’s demands, their unpopularity being one of the factors contributing to the outbreak of the Civil War in the following decade – and to Laud’s execution by order of Parliament in 1645! In 1653 the font was unceremoniously ejected from the church, the bowl finding a home in a farmyard and the stem in the garden of a riverside inn.

The 17th century communion fittings, with seating arranged around a central table.

In the 17th and 18th centuries, the congregation sat in a mixture of benches, pews and high-backed box pews, all replaced by pews (retaining earlier elements) in the restoration of 1861-62. There is some fine Victorian stained glass, including a window in the north wall of the north aisle by Clayton and Bell commemorating members of the Butterworth family, probably installed in the 1870s. The memorial window in the west wall of the north aisle (with panels in the tracery lights celebrating the Six Days of Creation including a dodo) commemorates the notable geologist Hugh Strickland (d. 1853); a coat of arms shows the turkey, an earlier member of the family – who from their base at Apperley Court acquired a large estate over the 19th century – being credited (rather dubiously) with bringing the first turkey from America. The architect William Slater directed the restoration of 1861-62: most of the roofs were rebuilt, most of the present pews (some reusing earlier ends) and the pulpit installed. The restoration took place at an early stage of the incumbency of the Rev. George Butterworth (1856 to 1893), during which time the font and its stem were returned to the church, Odda’s Chapel discovered in 1885 and then the apse excavated (see History) in 1890. In 1913–15 a controversial proposal to rebuild the apse was blocked by the Earl of Coventry who refused to sell the land.

Major repairs were carried out in the 1960s but are poorly documented. The plaster at the far east end of the north aisle was removed in the 1970s by Harold Taylor and others, exposing the 9th-century and later stonework. Most recently an extensive programme of liturgical reordering was implemented during the 2010s, with extensive contributions from the Friends.

Detail of the Strickland memorial window.

The Butterworth memorial window, by the London form of Clayton and Bell, probably dates from after 1872, the date of the death of the last figure commemorated in the plaque on the jamb of the window. George Butterworth also provided the grisaille glass in the high east window in 1861-2.

The finely crafted pulpit, dating from the restoration of 1861-62.